I love to read a good book. To me a truly good book is one that tells a great story in a beautiful way. One that speaks to you and keeps you thinking, even after you’re done reading. I just finished reading such a book.

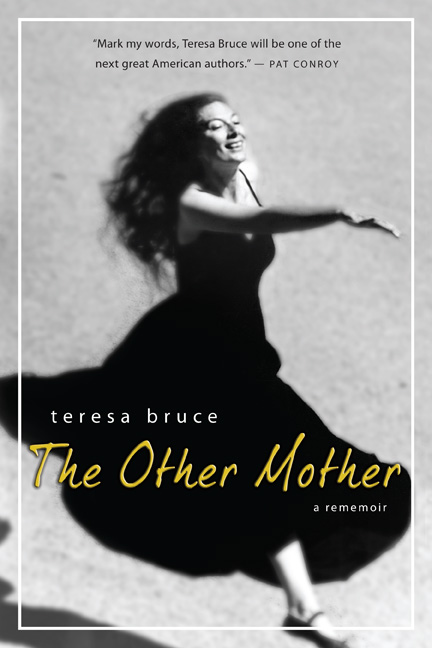

I was asked recently to review a book called “The Other Mother: A Rememoir” by Teresa Bruce.

In it, the author tells the story of her own young self and the woman she came to call her “other mother.” This woman, Byrne Miller, came of age during the depression. She was a dancer and dance instructor, a wife to a struggling author, and a mother to two biological daughters, one of which was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age five, the other killed in a car accident in adulthood. Teresa brings Byrne to life in her book and showcases the amazing spirit of the woman who “collected” children wherever she went, remarking, “If the family you’re given cannot make you happy, or vice versa, collect another.”

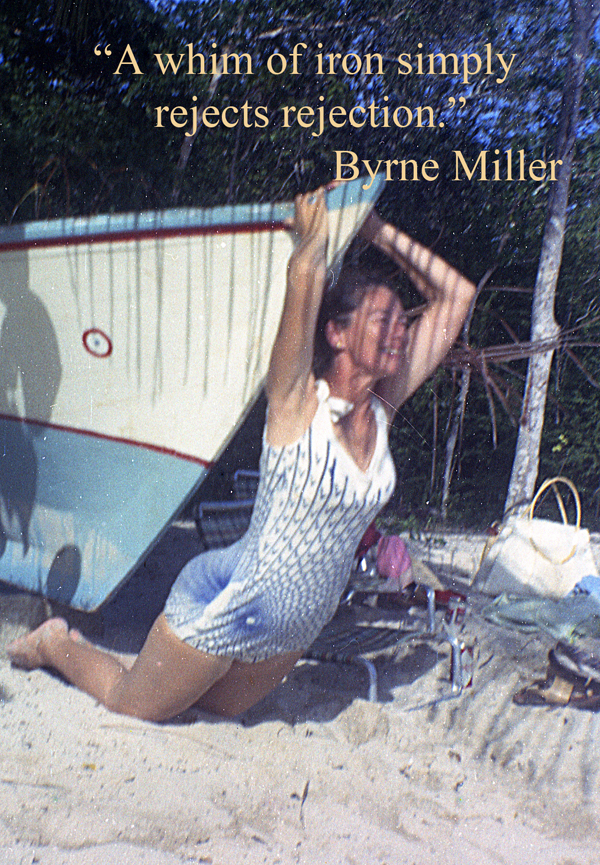

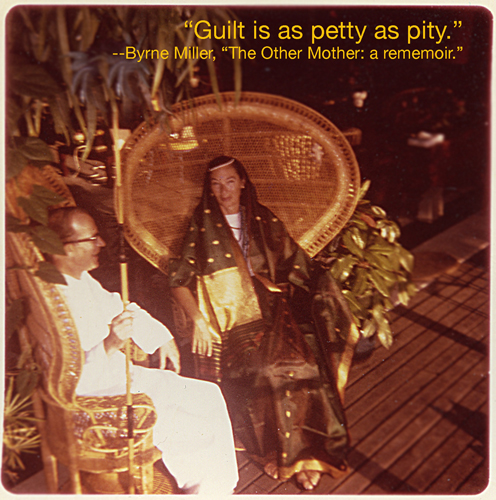

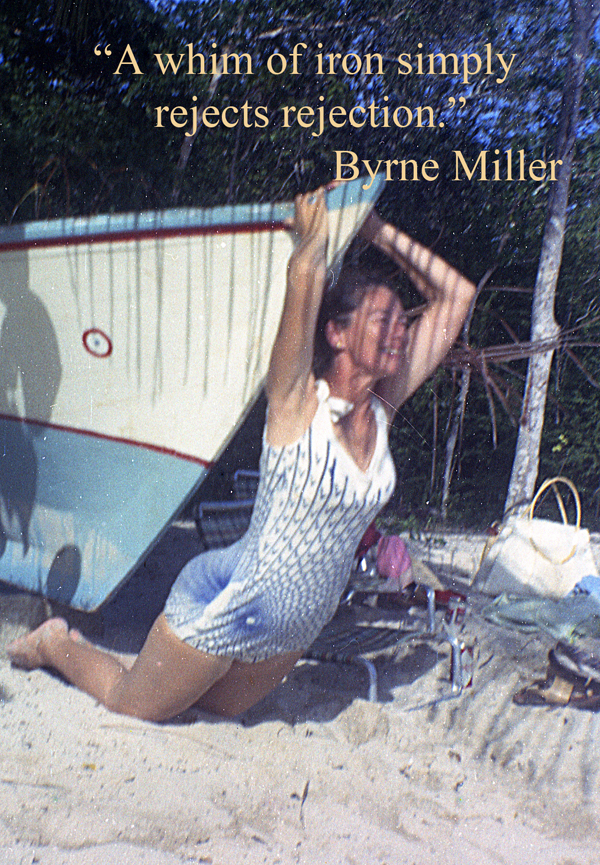

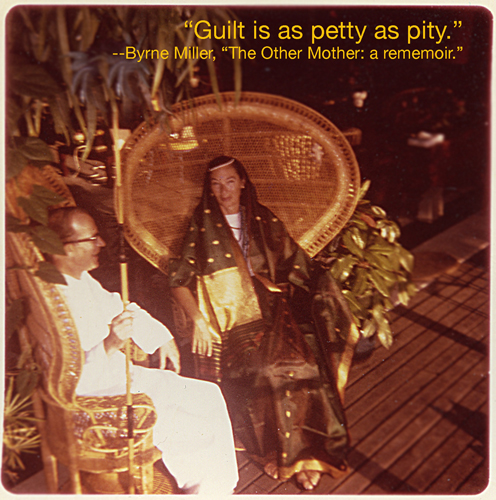

Teresa was one of Byrne’s collected daughters and she tells Byrne’s story with compelling honesty and insight. She refers to Byrne’s colorful comments and bits of advice as “womenisms,” and these are peppered throughout the book. As I read, I found myself captivated, experiencing a strong sense of connection with the unique and gutsy character of Byrne, in spite of the fact that she was of another generation and lived a life vastly different from mine.

I really loved this book, but I struggled with figuring out how to write a review because of one major aspect of Byrne’s life. Not long after their daughter’s diagnosis with schizophrenia, Byrne catches her husband Duncan having a secret affair, and upon confronting him, learns that he wants to have an “open” marriage.

“He wanted an arrangement,” Teresa writes, “an escape hatch from the broken child he could not fix.” Byrne accommodates him, stipulating that they must always at least be honest about it. One of the womenisms attributed to Byrne is, “Monogamy is overrated. Honesty is imperative.” Another is, “Every woman should have at least one affair. It builds confidence.”

I vehemently disagree with both of these statements (except the second part of the first one). So much so that I had a hard time reconciling my dislike of statements like these with my love of the book and with the character of Byrne.

There is so much more to this book and to Byrne than this piece of the story, but it was hard for me to figure out how to write about it because of that one part that I feel so uncomfortable with. Obviously, the book and the author are not advocating having affairs or open marriages. But… I got stuck on this issue when trying to find a way to formulate my review.

For one thing, I could not connect with the character of Duncan, in spite of feeling empathy about his having Alzheimer’s and the inclusion in the book of several moving passages about his love for Byrne. For another, I couldn’t get on board with the portrayal at points in the book of Byrne and Duncan’s relationship as being so amazing and wonderful. A few times in the book, Teresa writes about one of Byrne’s daughters “finding her Duncan” as a metaphor for finding the perfect man. Knowing that he cheated on Byrne throughout their marriage, I could not understand why anyone would want to “find a Duncan.”

Teresa was very open to discussing the book with me and answering questions through email, so I expressed my feelings about this to her. She noted that she didn’t think Byrne’s advice to have affairs was meant to be taken literally (though Byrne did have at least two affairs herself in her open marriage, as described in the book). Teresa also commented that she knew the open marriage thing would probably be a hard part of the story for many women to swallow. In an email to me she wrote, “As a ‘daughter’ of Byrne I kind of wanted to protect that part of her story, but as a writer, I thought I had to include it because it was part of my journey of going from thinking [Byrne and Duncan] had a perfect, fairy-tale life and marriage to realizing the truth.“

That last statement was a great way to sum up the progression of the book around this topic. It reminded me that saying that someone had found “her Duncan” wasn’t so much saying she had found the perfect man, but that she had found the perfect man for her. And though their marriage was far from ideal, Duncan seemed to be the perfect mate for Byrne, and she for him. They seemed to understand and complement each other and to truly love each other in a way that worked for them. Teresa also pointed out her own dedication of the book to her husband, “For Gary, the man Byrne always knew was out there for me.” NOT, “For Gary – my Duncan.”

As Teresa reveals poignantly, Byrne’s life was anything but a fairy tale. Her older (biological) daughter Alison was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age five, and her younger daughter was killed by a drunk driver. Her husband had Alzheimer’s. And there was much more, but I don’t want to spoil some twists in the story.

For me the most haunting chapter in the book was the one in which Teresa describes the time when Alison was diagnosed, and Byrne reluctantly agreed to allow her to undergo electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Byrne was devastated, feeling she had betrayed her daughter by allowing this treatment. But also, in 1943, she was shouldering the blame for her daughter’s illness, as it was still thought at that time that schizophrenia was caused by a “schizophrenogenic mother.”

After the ECT failed to produce desired results, the doctors suggested Alison be institutionalized. My favorite line of the book follows this, “‘Speak again of taking my child away from me,’ [Byrne] threatened, a cobra about to strike, ‘and I will attach those ECT wires to your testicles.’” I wanted to cheer when I read this. And I wanted to cry. I could absolutely see myself saying something similar if I felt one of my children was being threatened. At the same time, I couldn’t imagine being in that position.

As a mother, I devoured the parts of the book about Byrne’s efforts to “cure” Alison herself. She was like a one-woman army, going into battle with a mysterious and elusive enemy to save her daughter’s mind. As a psychologist, I cannot imagine that struggle. Obviously no one (not even the most dedicated mother) can cure schizophrenia through hard work and sheer force of will, but Byrne did help Alison to be able to attend regular schools and function throughout her life mostly independently.

One of the womenisms Teresa attributes to Byrne is, “When what is painful can’t be fixed, close the door behind you and walk into another room. The brain has more chambers than the heart.” Byrne seemed to me the perfect example of the saying, “When life hands you lemons, make lemonade.” She did not dwell on hardship, but made the most of whatever situation life handed her.

Reading about why she made the choices she did, how she made them work, and what she learned from them was something I really loved about the book. I especially enjoyed reading about some of Byrne’s unorthodox parenting choices, which I found both amusing and challenging.

For example, when Duncan quit a job and suggested they leave New York for someplace quieter so he could write, they went to Byrne’s aunt’s old country home, only to find that the actual house was gone and all that was left was a chicken coop and a tree house. Byrne allowed her daughters to live in the treehouse, while putting a tent around the chicken coop for herself and Duncan. Yes, you read that right. She allowed her two young daughters to live in a treehouse.

This cracked me up at the same time it kind of horrified me. I would never allow my girls to live in a treehouse (entertaining as it was to read about someone who did), but reading about Byrne’s way of finding unconventional solutions challenged me and spoke to the part of me that knows I need to lighten up about many things with my own girls.

And therein lies the beauty of this book. If you are a woman, it speaks to you. It speaks to mothers, daughters, wives, sisters, and friends. It speaks to anyone who finds joy in self expression and art and movement. It speaks to those who have lost loved ones, whether through death or descent into psychosis and/or dementia. It speaks to anyone who has made bad decisions and to everyone who would do anything for her family, biological or “collected.”

The parts of the story that I felt most connected to, naturally, had to do with Byrne’s struggles and triumphs as a young mother. But I also appreciated the grit and spirit of this woman who fought for her children and for her marriage, even if it was often in unusual ways.

The relationship between Teresa and Byrne is one I find to be a model of how women can and should always have a support system of other women, whether that comes from blood relatives or others. I have written before about how everyone should have a Super Friend. I guess I could even refer to Super Friend as my “Other Sister.” But Teresa brings up another relationship that is critically important also, that of a mother. She reminds us that we can have this relationship even when our own mother does not or cannot provide it.

Women can and should bring out the best in each other. This book provides such a beautiful portrait of one way this can occur. If you’re a woman, you should absolutely read this book. And then email me and tell me what you thought, because I am dying to talk to someone about it! Get a copy, or win it here!

Again I have an opportunity to give away a copy of this book. This time, I have in my possession an autographed hardcover copy that I can’t wait to send to someone who will enjoy it. So, like last time just leave a comment to enter. I’ll pick a winner (via Random.org) on Monday, December 16th at 9pm Central time.

Have you ever had an “other mother” or another woman outside your family who meant as much to you as your biological relatives? Have you been an “other mother”?

** Disclosure – I was given a two signed copies of this book in exchange for writing a review of it.