I think it’s a fairly common belief of people who are not Catholic (and also some who are) that the sacrament of Reconciliation, or confession, is totally unnecessary. I know that I used to think, “Why do I need to confess my sins to a priest? I can just confess directly to God and ask forgiveness.” I also kind of thought it was creepy and weird that priests would encourage people to tell all of their deepest, darkest, secrets (says the woman who used to be a clinical psychologist) and then give them a penance to complete afterwards.

Of course there is Biblical support for the practice of confessing one’s sins to God.

Blessed is the one whose fault is removed, whose sin is forgiven. Blessed is the man to whom the Lord imputes no guilt, in whose spirit is no deceit. Because I kept silent, my bones wasted away; I groaned all day long. For day and night your hand was heavy upon me; my strength withered as in dry summer heat. Then I declared my sin to you; my guilt I did not hide. I said, “I confess my transgressions to the Lord,” and you took away the guilt of my sin. – Psalm 32:1-7

The Catholic Church does not dismiss the value of making a regular confession of one’s sins directly to God. I do this every day during my daily prayers, and I know a lot of Catholics go through the examination of conscience each day for this same purpose. The examination of conscience is something Catholics (ideally) go over before going to reconciliation, to assist in making a good confession, but many also use it for confessing directly to God in prayer. You can see an example here.

So sure, confessing directly to God is important, and valid, and necessary. But the sacrament of Reconciliation is a whole different ballgame.

Let’s start with the Biblical basis for the practice. In the book of John, when Jesus appears to the apostles in the locked room after His resurrection:

[Jesus] said to them again, “Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, so I send you.” And when he had said this, he breathed on them and said to them, “Receive the Holy Spirit. Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them, and whose sins you retain are retained.” – John 20:21-23

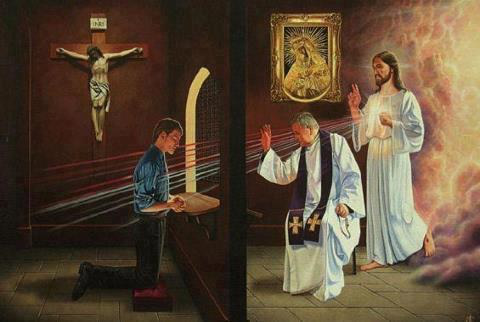

So, in the Bible, Jesus gave the apostles, the first priests of His Church, the authority to forgive sins. They do this by acting in persona Christi, or in the person of Christ. I mentioned in my post about the priesthood that there are two types of situations in which priests are given the special authority to act in the person of Christ: 1. during the act of transubstantiation in the Mass, or when the priest turns the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, and 2. during the sacrament of Reconciliation. So really, priests don’t personally have the authority to forgive sins, but they have the authority to act as Christ during the sacrament of Reconciliation, and as such, forgive sins.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church says, “Only God forgives sins. Since he is the Son of God, Jesus says of himself, ‘The Son of man has authority on earth to forgive sins’ and exercises this divine power: ‘Your sins are forgiven.’ Further, by virtue of his divine authority he gives this power to men to exercise in his name.” (1441)

The sacrament of Reconciliation has been practiced in various forms throughout the centuries, with the very early Church instituting penances that were public and sometimes severe and lengthy in nature. It was during the seventh century that Irish missionaries took the practice of private confession and penance to continental Europe, and the sacrament has been performed in private ever since.

As the Church practices it currently, it goes pretty much like this: Parishioner goes into the confessional (which in our parish is just a little room with comfy chairs to sit on), sits down and says, “Bless me father, for I have sinned. It has been (however long) since my last confession.” Ideally, parishioner will have gone through an examination of conscience beforehand and will then be able to proceed to provide a pretty comprehensive list of sins for the priest. After this is done, the parishioner says the Act of Contrition:

Image credit Prayer Button

Then the priest, acting in persona Christi, gives a penance to the parishioner (perhaps a number of prayers to say or an act of restitution to perform), may say a blessing, and ends with something like, “I absolve you from your sins, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

So, now that I’ve given you a little bit of the history of confession and how it works, I’ll tell you about my very limited but powerful experience with the sacrament.

I have only been to confession once, the Wednesday before Holy Saturday. All of my praying life, pre- and post-atheism, I have included confession of my sins to God in my daily prayers (okay, pre-atheism they were rarely daily. . .). So I thought it would be pretty straightforward to do an examination of conscience and go in and confess my sins to our priest. Yes, I was nervous, because I was confessing a whole lifetime of sins, face to face with the man who stands in front of our church pretty much every Sunday. I had a lot of stuff to confess from my whole life. But again, I had confessed most of it directly to God in prayer after my conversion, so it wouldn’t be too hard, right?

Well, first of all, the examination of conscience had me questioning myself about many behaviors, thoughts, and omissions that I never would have thought to confess or even think of as true sins before preparing for confession. So I had to face up to lots of things I had done or failed to do that I hadn’t even realized I needed to confess.

Then I went into the confession room with our priest. I was very nervous, and as I began my confession, I was kind of shocked by how much harder it was to speak my sins out loud to another person than to say them in my head during my prayers. I do truly try to focus on being repentant when I pray about my sins, but somehow saying them out loud to anther person made me so much more so.

I got through all of my fairly distant sins of the past and the more recent ones during my atheist years, and that was hard. But the hardest part by far was confessing my current day to day transgressions. The “smaller” sins that I grapple with in my everyday life, like using an unkind voice with my husband, feeling anger toward my children, being impatient, snapping at my kids, acting selfishly, and so on. I was struggling not to cry when I began telling my priest about some of my ugly behaviors and thoughts, things that I do now, not in the distant past.

When I got to the Act of Contrition, I could barely get the words out. “But most of all because they offend thee my God, who art all-good and deserving of all my love” was nearly impossible to say through the lump in my throat and over the sobs threatening to escape from my mouth. I suddenly felt the full impact of my sins, and how offensive they are to God, and I was appalled.

After I got through the whole prayer and the priest said, “I absolve you from your sins, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” it was a really amazing moment. I truly felt a sense of relief and joy after my time in the confessional, and even more so after completing my penance.

So many people seem to associate the idea of confession with negative emotions, beliefs, and experiences. But here’s what I believe about it: Confession isn’t something the Church created for the purpose of controlling and manipulating people. It is a gift that Jesus gave to us to help us experience His forgiveness more fully.

And it works.

I haven’t decided on the next topic yet. If you have a question, let me know.

One thought on “Baby Catholic Answers All the Things, Volume 4 – Confession”